Vybrané partie z dátových štruktúr

2-INF-237, LS 2016/17

Táto stránka sa týka školského roku 2016/17. Od školského roku 2017/18 predmet vyučuje Jakub Kováč, stránku predmetu je https://kubokovac.eu/ds/

Poradie tém, poznámky, prezentácie:

Úvodné informácie

- Niektoré prednášky budú v angličtine, domácu úlohu, prezentáciu a skúšku však môžete robiť aj po slovensky.

Základné údaje

Rozvrh

- Uto 9:50-11:20 M-VIII

- Str 15:40-17:10 M-II

Vyučujúca

Ciele predmetu

- Oboznámime sa s dátovými štruktúrami nepreberanými na základných

bakalárskych predmetoch a s metódami ich analýzy. Zhrnieme tiež základné

algoritmy na vyhľadávanie vzorky (slova) v texte.

- Použitie a prehĺbenie znalostí z predchádzajúcich predmetov

týkajúcich sa tvorby a analýzy efektívnych algoritmov a dátových

štruktúr.

- Získavanie skúseností v práci s odbornou literatúrou, navrhovaní a vyhodnocovaní výpočtových experimentov.

Literatúra

- Dan Gusfield (1997) Algorithms on Strings, Trees and Sequences: Computer Science and Computational Biology. Cambridge University Press. Prezenčne v knižnici so signatúrou I-INF-G-8.

- Obsahuje časť učiva o sufixových poliach a stromoch

- Cormen, Thomas H., Charles E. Leiserson, Ronald L. Rivest, and

Clifford Stein. Introduction to Algorithms. MIT Press 2001. Prezenčne v

knižnici so signatúrou D-INF-C-1.

- Obsahuje napríklad amortizovanú analýzu

- Peter Brass. Advanced Data Structures. Cambridge University Press 2008. Prezenčne v knižnici so signatúrou I-INF-B-67

- Poznámky z predmetu Vyhľadávanie v texte [1]

- Obsahujú časti súvisiace s textom (vyhľadávanie kľúčových slov,

sufixové polia a stromy, LCA a RMQ, BWT, KMP, editačné vzdialenosť), ale

sú zčasti písané študentami a nedokončené

- Gnarley trees Stránka Kuka Kováča a jeho študentov s vizualizáciou dátových štruktúr

- MIT predmet Advanced Data Structures vyučovaný Erikom Demainom

- Ďalšiu literatúru uvedieme k jednotlivým témam

Prezentácia

Cieľom prezentácie je precvičiť si prácu s odbornou literatúrou a

oboznámiť sa s ďalšími výsledkami v oblasti dátových štruktúr. Každý

študent si zvolí a podrobne naštuduje jeden odborný článok (z odbornej

konferencie alebo časopisu) z tejto oblasti a ten odprezentuje

spolužiakom na prednáške koncom semestra. Každý študent si musí zvoliť

iný článok.

Termíny

- Výber článku na prezentáciu do pondelka 24.4. v systéme Moodle.

Každý článok môže prezentovať iba jeden študent, takže odovzdajte svoj

výber radšej skôr. Kto si článok do uvedeného termínu nevyberie, bude mu

nejaký priradený vyučujúcou.

- Prezentácie na prednáškach v posledných týždňoch semestra

- Prezentáciu vo formáte pdf odovzdať prostredníctvom Moodlu najneskôr 1 hodinu pred prednáškou, na ktorej máte prezentovať.

Rozvrh prezentácií

Rady k prezentácii

- Na prezentáciu budete mať 15 minút (plus diskusia), pričom tento

limit bude striktne dodržiavaný. Nechystajte si teda priveľa materiálu,

rátajte aspoň 1,5 minúty na slajd.

- K dispozícii bude dátový projektor a notebook, na ktorom bude

nahraná vaša odovzdaná prezentácia. Môžete si priniesť aj vlastný

počítač. Môžete použiť tabuľu, ale s mierou, lebo vysvetľovanie pri

tabuli ide pomalšie.

- Hlavným cieľom je porozprávať niečo zaujímavé z vášho článku vo

forme prístupnej vašim spolužiakom (ktorí chodili na tento predmet,

nepamätajú si však každý detail z každej prednášky). Nemusíte pokryť

celý obsah článku a nemusíte použiť rovnaké poradie, označenie alebo

príklady, ako autori článku.

- Nedávajte do prezentácie veľa textu, použite dostatočne veľký font a

dobre viditeľné farby (podobné farby, napr. žltá na bielej, nemusia byť

na projektore vôbec viditeľné).

- Použite čo najmenej definícií a označenia. Pojmy, algoritmy a

dôkazy radšej ilustrujte na obrázku alebo príklade, než zložitým textom.

Typická osnova prezentácie (podľa potreby ju však možete meniť):

- Úvod: aký problém autori študujú, prečo je dôležitý alebo

zaujímavý? Má nejaký vzťah k učivu z prednášok, prípradne k iným

predmetom?

- Prehľad výsledkov: V čom je presne prínos autorov oproti

predchádzajúcim prácam? Nemusíte robiť rozsiahly prehľad

predchádzajúcich prác, len uveďte, čo je v článku nové. Malo by to byť

jasné najmä z úvodu a záveru článku.

- Jadro: Vysvetlite nejaký kúsok zo samotného obsahu článku (časť

algoritmu alebo dôkazu, niektoré výsledky z testovania na dátach a pod.)

- Záver: zhrnutie prezentácie, váš názor (čo sa Vám na článku páčilo alebo nepáčilo)

Typy vhodných článkov

- Články o dátových štruktúrach alebo ich variantoch, ktoré neboli/nebudú pokryté na prednáške

- Články empiricky porovnávajúce dátové štruktúry na reálnych dátach

alebo popisujúce použitie týchto algoritmov v reálnych aplikáciach.

- Články o podrobnejšej analýze dátových štruktúr: dolné a horné odhady, analýza v priemernom prípade a pod.

Príklady článkov

Zopár ukážok článkov, nemusíte si však vybrať z tohto zoznamu.

- Andoni A, Razenshteyn I, Nosatzki NS. Lsh forest: Practical algorithms made theoretical. SODA 2017 [2]

- Alstrup, Stephen, Cyril Gavoille, Haim Kaplan, and Theis Rauhe.

"Nearest common ancestors: A survey and a new algorithm for a

distributed environment." Theory of Computing Systems 37, no. 3 (2004):

441-456. [3] Tento článok je už obsadený.

- Gonzalo Navarro, Yakov Nekrich: Optimal Dynamic Sequence Representations. SODA 2013: 865-876 [4]

- Holm, Jacob, Kristian De Lichtenberg, and Mikkel Thorup.

"Poly-logarithmic deterministic fully-dynamic algorithms for

connectivity, minimum spanning tree, 2-edge, and biconnectivity."

Journal of the ACM (JACM) 48, no. 4 (2001): 723-760. pdf Ako

udržiavať súvislé komponenty v dynamickom grafe. Dlhší článok, stačí

naštudovať a prezentovať časť o súvislosti a aj tá je pomerne náročná.

- Wild, Sebastian, and Markus E. Nebel. "Average case analysis of Java 7’s dual pivot quicksort." ESA 2012, pp. 825-836. [5] Síce ide o triedenie a nie dátové štruktúry, ale tieto dve oblasti spolu úzko súvisia. Tento článok je už obsadený.

- Goel, Ashish, Sanjeev Khanna, Daniel H. Larkin, and Robert E. Tarjan. "Disjoint Set Union with Randomized Linking." SODA 2014 [6]

- Bender, Michael A., Roozbeh Ebrahimi, Jeremy T. Fineman, Golnaz

Ghasemiesfeh, Rob Johnson, and Samuel McCauley. "Cache-Adaptive

Algorithms." [7] Zovšeboecnenie modelu cache-oblivious algoritmov.

- Arge L, Bender MA, Demaine ED, Holland-Minkley B, Munro JI.

Cache-oblivious priority queue and graph algorithm applications. In

Proceedings of the thiry-fourth annual ACM symposium on Theory of

Computing 2002 May 19 (pp. 268-276). ACM. [8]

- Bonomi, F., Mitzenmacher, M., Panigrahy, R., Singh, S., &

Varghese, G. (2006). An improved construction for counting Bloom

filters. In Algorithms–ESA 2006 (pp. 684-695). Springer. [9] Tento článok je už obsadený.

- Song H, Dharmapurikar S, Turner J, Lockwood J. Fast hash table

lookup using extended bloom filter: an aid to network processing. ACM

SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review. 2005 Oct 1;35(4):181-92. [10]

Kirsch A, Mitzenmacher M. Less hashing, same performance: building a better bloom filter. ESA 2006 (pp. 456-467). Springer [11]

- Winter C, Steinebach M, Yannikos Y. Fast indexing strategies for

robust image hashes. Digital Investigation. 2014 May 31;11:S27-35. [12] Tento článok je už obsadený.

- Bender, Michael A., and Martın Farach-Colton. The level ancestor

problem simplified. Theoretical Computer Science 321.1 (2004): 5-12. pdf Tento článok je už obsadený.

- Belazzougui D. Linear time construction of compressed text indices in compact space. STOC 2014 [13]

- Darragh JJ, Cleary JG, Witten IH. Bonsai: a compact representation

of trees. Software: Practice and Experience. 1993 Mar 1;23(3):277-91. [14] Tento článok je už obsadený.

- Gawrychowski P, Nicholson PK. Optimal Encodings for Range Top-k, Selection, and Min-Max. ICALP 2015 [15]

- Chan TM, Wilkinson BT. Adaptive and approximate orthogonal range counting. SODA 2013 [16]

- Dumitran M, Manea F. Longest gapped repeats and palindromes. MFCS 2015 [17]

- Ferragina P, Grossi R. The string B-tree: a new data structure for

string search in external memory and its applications. JACM 1999 [18]

- Belazzougui D, Gagie T, Gog S, Manzini G, Sirén J. Relative FM-indexes. SPIRE 2014 [19] Tento článok je už obsadený.

- Hon WK, Shah R, Vitter JS. Space-efficient framework for top-k string retrieval problems. FOCS 2009. [20] Tento článok je už obsadený.

- Jannen, William, et al. "BetrFS: A right-optimized write-optimized

file system." 13th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies

(FAST 15). 2015. [21] Tento článok je už obsadený.

- Gog S, Moffat A, Petri M. CSA++: Fast Pattern Search for Large Alphabets. ALENEX 2017 [22]

- Hansen TD, Kaplan H, Tarjan RE, Zwick U. Hollow Heaps. arXiv preprint arXiv:1510.06535. 2015 [23] Tento článok je už obsadený.

- Ferragina, Paolo, Raffaele Giancarlo, and Giovanni Manzini. "The

engineering of a compression boosting library: Theory vs practice in BWT

compression." European Symposium on Algorithms. 2006. [24] Tento článok je už obsadený.

- Gog S, Petri M. Optimized succinct data structures for massive

data. Software: Practice and Experience. 2014 Nov 1;44(11):1287-314.

[25] Tento článok je už obsadený.

- Moffat A, Gog S. String search experimentation using massive data.

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A:

Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 2014 [26]

Články navrhnuté študentami

- Rubinchik M, Shur AM. EERTREE: an efficient data structure for

processing palindromes in strings. In International Workshop on

Combinatorial Algorithms 2015 Oct 5 (pp. 321-333). [27] Tento článok je už obsadený.

- Stefanov E, Papamanthou C, Shi E. Practical Dynamic Searchable

Encryption with Small Leakage. In NDSS 2014 Feb (Vol. 71, pp. 72-75). [28] Tento článok je už obsadený.

Rady k hľadaniu článkov

- Podľa kľúčových slov sa články dobre hľadajú na Google Scholar. Tam okrem iného nájdete aj linky na iné články, ktoré daný článok citujú, čo môže byť dobrý zdroj ďalších informácií.

- The DBLP Computer Science Bibliography

je dobrý zdroj bibtexových záznamov, ak píšete projekt alebo inú prácu v

Latexu a tiež sa dá použiť na nájdenie zoznamu článkov od jedného

autora alebo z jednej konferencie a podobne.

- Konferencie CPM a SPIRE sú dobrým zdrojom článkov o vyhľadávaní v

texte, iné dátové štuktúry nájdete na všeobecných konferenciách pre

teoretickú informatiku, napr STOC, FOCS, SODA. ESA. WADS, MFCS, ISAAC.

Praktické implementácie sú námetom konferencií WAE a ALENEX.

Väčšina databáz má linky na elektronické verzie článkov u vydavateľa.

Tam väčšinou uvidíte aspoň voľne prístupný abstrakt, ktorý vám pomôže

rozhodnúť, či Vás článok zaujíma. Pre niektoré zdroje (napr. ACM, IEEE a

ďalšie)

je plný text článku prístupný z fakultnej siete. Z domu sa môžete

prihlásiť cez univerzitný proxy (v prehliadači nastavte automatický

konfiguračný skript http://www.uniba.sk/proxy.pac

). Celý text článku (pdf) sa v mnohých prípadoch dá nájsť na webe

(napr. na webstránke autora). V najhoršom prípade, ak neviete zohnať

článok, ktorý k projektu alebo prezentácii veľmi potrebujete,

kontaktujte ma e-mailom a môžem sa pokúsiť ho zohnať.

Poznámky

Táto stránka obsahuje pokyny k písaniu poznámok na wiki.

Kontá

Ak chcete poznámkovať, vypýtajte si e-mailom konto od vyučujúcej.

Vaše užívateľské meno bude užívateľské meno z AIS (napr. mrkvicka37).

Ako email budete mať nastavenú univerzitnú adresu (napr.

mrkvicka37@uniba.sk). Heslo si môžete dať poslať na túto adresu a potom

si ho zmeniť podľa vlastného výberu.

Bodovanie

- Pri robení väčších úprav na jednej stránke dostanete body za tieto úpravy

- Pri menších opravách budem kumulovať body za celkovú aktivitu tohto

typu v rámci semestra (na wiki neplatí, že každá opravená chyba je

jeden bod)

- Body budem zapisovať do Moodla, pokúsim sa v komentári uviesť, čo zahŕňajú

- Ak máte pocit, že som niektoré vaše úpravy zabudla obodovať, dajte mi vedieť

Štýl poznámok

- Poznámky sú rozdelené do tematických celkov, ktoré nezodpovedajú

striktne prednáškam (jedna téma môže mať viac prednášok alebo naopak

jedna prednáška môže zahŕňať viac tém).

- Zoznam tém na hlavnej stránke vytvára vyučujúca, nemeňte ho.

- Ideálne pre každú tému budeme mať súvislý text v angličtine (príp. v

slovenčine) pokrývajúci väčšinu prednášky, ilustrovaný vhodnými

obrázkami a doplnený odkazmi na ďalšie zdroje informácií.

- Po obsahovej stránke sa držte prednášky, vrátane použitého

označenia a pod. Ak chcete pridať vlastné poznámky, ktoré neboli na

prednáške, zreteľne ich vyznačte, podpíšte vlastným menom a pokiaľ možno

uveďte zdroje informácií.

- K cvičeniam a nepovinným úlohám riešeným na prednáške uveďte

zadanie a prípadne krátku nápovedu, ale nie celé riešenie. Nápovedy

umiestnite na koniec textu témy, nie hneď za zadanie.

- Vyučujúca môže ako štartujúci materiál k textu poskytnúť stručné

poznámky prípadne v inom formáte (latex apod.) Takýto štartovací

materiál môžete pokojne upravovať do výsledných poznámok.

- Takisto môžete zlepšovať poznámky spísané vašimi spolužiakmi,

počkajte však určitý čas od ich zverejnenia, nakoľko ich autor možno na

nich ešte pracuje.

- Ak na wiki pridávate obrázky, nahrajte výsledný obrázok vo formáte

png, gif, jpg, alebo svg. Ak ste však obrázok vytvárali nejakým

programom, ktorý používa iný formát ako zdrojový, nahrajte prosím aj

súbor s rovnakým menom ale príponou zip, obsahujúci tieto zdrojové

súbory a krátky README, aby ďalšie osoby mohli tento obrázok v

budúcnosti editovať.

Autorské práva

- Texty a obrázky na stránke by mali byť vaše vlastné, vytvorené na

základe prednášok prípadne úpravou materiálov, ktoré už sú na stránke.

- Nepridávajte texty a obrázky z iných zdrojov, jedine ak by boli

voľne šíriteľné (public domain). V takom prípade jasne uveďte zdroj.

- Vaše príspevky na wiki budú zverejnené s licenciou Creative Commons Attribution license 4.0

Ako editovať

Pravidlá

Stupnica

A: 90 a viac, B:80...89, C: 70...79, D: 60...69, E: 50...59, FX: menej ako 50%

Známkovanie

Sú tri alternatívy známkovacej stupnice:

| Alternatíva A |

Alternatíva B |

Alternatíva C |

- Aktivita počas semestra: 10%

- Domáca úloha: 15%

- Prezentácia článku: 15%

- Skúška: 60%

|

- Aktivita počas semestra: 10%

- Domáca úloha: 15%

- Prezentácia článku: 15%

- Projekt: 60%

|

- Aktivita počas semestra: 10%

- Prezentácia článku: 15%

- Projekt: 75%

|

Základná možnosť A je ukončená skúškou. Namiesto skúšky, alebo prípadne aj domácej úlohy môžete v alternatívach B a C robiť projekt, ale iba ak do 31.3.

oznámite e-mailom vyučujúcej, o ktorú alternatívu máte záujem a

dohodnete sa na predbežnej téme projektu. Projekty sú väčšinou časovo

náročnejšie ako príprava na skúšku, takže ich odporúčam len študentom,

ktorý majú o nejakú tému súvisiacu s predmetom veľký záujem. Projekty

sa budú odovzdávať cez skúškové obdobie (termín bude určený neskôr). Po

oznámkovaní projektu sa bude konať ešte krátka ústna skúška týkajúca sa

projektu, ktorá môže ovplyvniť vašu výslednú známku.

Body zo semestra môžete priebežne sledovať v systéme Moodle, cez ktorý budete aj odovzdávať domácu úlohu.

Skúška

Na termín sa hláste/odhlasujte v AISe najneskôr 14:00 deň pred

skúškou. Na skúške dostanete zadania niekoľkých príkladov, ktoré môžete

priebežne odovzdávať, v prípade väčšej chyby môžete ešte svoje riešenie

prerobiť, ale za chybné odovzdanie stratíte zopár bodov. Skúška bude

obsahovať nasledujúce typy príkladov:

- simulácia algoritmu prednášky na nejakom vstupe (nakreslite, ako

bude vyzerať dátová štruktúra, do ktorej sme vložili konkrétne prvky a

pod.)

- príklad, kde treba vymyslieť variáciu známeho algoritmu, analyzovať

jeho správanie na určitom type vstupu a pod. (podobné príklady budeme

občas robiť ako cvičenie na hodine)

- otázka k preberaným dátovým štruktúram (určité detaily alebo naopak zhrnutie)

Na skúške je povolený ťahák v rozsahu 2 listov formátu A4 s ľubovoľným obsahom.

Aktivita

Počas semestra študent môže získať body za aktivitu nasledovnými spôsobmi:

- Riešenie príkladu pri tabuli alebo odpovedanie otázky na hodine (0-3 body podľa obtiažnosti príkladu a správnosti odpovede)

- Nepovinné domáce úlohy (ústne alebo písomné)

- Nájdenie chyby na prednáške alebo v prezentácii (1 bod)

- Spísanie poznámok z prednášky na wiki, opravovanie chýb a

zlepšovanie existujúcich poznámok (Spísanie celej prednášky je max. 5

bodov, menšie úpravy a opravy dostanú body podľa kvality a rozsahu

zmien). Viac detailov k poznámkam na zvláštnej stránke.

Celkovo je možné za aktivitu získať najviac 20%, t.j. najviac 10% bonus ku známke.

Body za aktivitu môžete získavať aj počas skúškového opravovaním a

dopĺňaním poznámok, avšak najneskôr 12 hodín pred začiatkom vášho

termínu skúšky. Ak vám po skončení ústnej skúšky bude chýbať najviac 5

bodov do lepšej známky, môžete sa pred zápisom známky dohodnúť s

vyučujúcou, že v priebehu nasledujúcich 7 dní sa pokúsite chýbajúce body

týmto spôsobom získať.

Prezentácia

Cieľom prezentácie je precvičiť si prácu s odbornou literatúrou a

oboznámiť sa s ďalšími výsledkami v oblasti vyhľadávania v texte. Každý

študent si zvolí a podrobne naštuduje jeden odborný článok (z odbornej

konferencie alebo časopisu) z tejto oblasti a ten odprezentuje

spolužiakom na prednáške koncom semestra. Každý študent si musí zvoliť

iný článok.

Viac informácií na zvláštnej stránke.

Opisovanie

- Máte povolené sa so spolužiakmi a ďalšími osobami rozprávať o

domácich úlohách a stratégiách na ich riešenie. Kód, namerané výsledky

aj text, ktorý odovzdáte, musí však byť vaša samostatná práca. Je

zakázané opisovať kód z literatúry alebo z internetu a ukazovať svoj kód

spolužiakom. Domáce úlohy môžu byť kontrolované softvérom na detekciu

plagiátorstva.

- Počas skúšky môžete používať iba povolené pomôcky a nesmiete komunikovať s žiadnymi osobami okrem vyučujúcej.

- V projekte musíte citovať všetku použitú literatúru. Zapíšte

získané poznatky vlastnými slovami. Nekopírujte z literatúry a iných

zdrojov celé vety (výnimkou môžu byť len krátke priame citáty s uvedením

zdroja). Obrázky pokiaľ možno vytvorte vlastné a pri prevzatých

obrázkoch uveďte zdroj, z ktorého pochádzajú.

- Ak nájdem prípady opisovania alebo nepovolených pomôcok, všetci

zúčastnení študenti získajú za príslušnú domácu úlohu, písomku a pod.

nula bodov (t.j. aj tí, ktorí dali spolužiakom odpísať). Opakované alebo

obzvlášť závažné prípady opisovania budú podstúpené na riešenie

disciplinárnej komisii fakulty.

Sylabus na skúšku

Na tejto stránke je sylabus na skúšku v školskom roku 2016/17

(neobsahuje úplný obsah všetkých prednášok)

Úsporné dátové štruktúry

- štruktúra pre rank a select

- wavelet tree

- štruktúra RRR a jej súvis s entropiou

- úsporné stromy, počet binárnych stromov

Amortizovaná zložitosť

- definícia amortizovanej zložitosti, potenciálová funkcia

Prioritné rady

- Fibonacciho halda a jej amortizovaná analýza

RMQ a LCA

- jednoduché algoritmy

- algoritmy s O(n) predspracovaním a O(1) dotazom

- segmentové/intervalové stromy

Scapegoat stromy, splay stromy a link-cut stromy

- scapegoat stromy, vrátane analýzy

- splay stromy (algoritmus, zložitosť a potenciálová funkcia, netreba celý dôkaz)

- použitie splay stromov na join a split

- link-cut stromy (štruktúra, expose, netreba analýzu zložitosti)

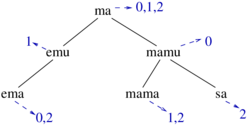

Vyhľadávanie kľúčových slov

- invertovaný index

- lexikografický strom

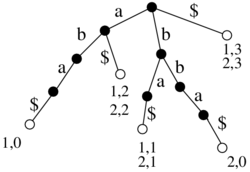

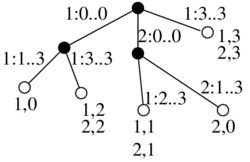

Sufixové stromy a polia

- sufixový strom

- sufixové pole

- vyhľadávanie vzorky v sufixovom strome a poli

- lineárny algoritmus na konštrukciu sufixového poľa

- konverzia zo sufixového poľa na sufixový strom a naopak

- použitie sufixového stromu a lca na hľadanie približných výskytov vzorky pri Hammingovej vzdialenosti

Burrowsova–Wheelerova transformácia

- vytváranie, spätná transformácia, použitie na kompresiu, FM index

Vyhľadávanie vzorky v texte

- triviálny algoritmus na presné výskyty

- použitie konečných algoritmov, Morrisov-Prattov a Knuthov-Morrisov-Prattov algoritmus

- dynamické programovanie na výpočet editačnej vzdialenosti a na hľadanie približných výskytov vzorky

Hešovanie

- Perfektné hešovanie: algoritmus, odhad očakávanej veľkosti pamäte pri použití univerzálnej triedy hešovacích funkcií

- Bloomov filter - algoritmus, približný odhad pravdepodobnosti chyby

Štruktúry pre externú pamäť

- výpočtový model externej pamäti, cache oblivious model

- B-stromy

- statické cache-oblivious stromy s vEB rozložením

Štruktúry pre celočíselné kľúče

- van Emde Boas stromy, x-fast trie, y-fast trie

Streaming model

- count-min sketch vrátane odhadu chyby

Perzistentné dátové štruktúry

- definícia (čiastočne a úplne) perzistentných a retroaktívnych dátových štruktúr

- všeobecné transformácie dátovej štruktúry na čiastočne perzistentnú (fat nodes, node copying)

- úplná retroaktivita pre problém nasledovníka (successor) a podobné rozložiteľné vyhľadávacie problémy

Geometrické dátové štruktúry

- lokalizácia bodu v rovine (planar point location) pomocou perzistentných a retroaktívnych štruktúr

- rozsahové stromy (range trees) a ich zrýchlenie (layered range trees)

- využitie wavelet trees namiesto statických rozsahových stromov

Nepovinná DÚ

Nepovinné domáce úlohy môžete použiť na získanie bodov za aktivitu aj

mimo prednášky. V rámci semestra bude ešte aspoň jedna ďalšia séria úloh,

ale nespoliehajte sa na to, že ich ešte bude veľa. Celkovo máte v hodnotení za body za aktivitu 10 bodov

a môžete získať ďalších 10 ako bonus.

Maximálny počet bodov je orientačný, ak sa úloha ukáže

náročnejšia, než sa očakávalo, môže byť zvýšený. O úlohách sa môžete

rozprávať, ale nepíšte si z takýchto rozhovorov poznámky a napíšte

text vlastnými slovami. Pri väčšine úloh preferujem vaše vlastné

riešenie, ale ak riešenie nájdete v literatúre, uveďte zdroj a napíšte

riešenie vlastnými slovami. Všetky odpovede zdôvodnite.

Séria 2, odovzdať najneskôr deň pred skúškou do 10:00

Nepovinnú domácu úlohu môžete odovzdať písomne v M163 (ak tam nie

som, strčte papier pod dvere) alebo emailom v pdf formáte a môžete za ňu

dostať body za aktivitu. Všetky odpovede stručne zdôvodnite.

Úloha 1 (2 body)

Uvažujme Morissov-Prattov algoritmus pre vzorku P dĺžky m, ktorý

bežíme na veľmi dlhom texte T. Koľko najviac bude trvať spracovanie

úseku dĺžky k niekde uprostred textu T ako funkcia parametrov m a k?

Hodnota k môže byť menšia alebo väčšia ako m. Uveďte asymptotický horný

aj dolný odhad, t.j. aj príklad, kde to bude trvať čo najdlhšie (príklad

by mal fungovať pre všeobecné m a k, ale môžete si zvoliť T a P a aj

ktorý úsek T dĺžky k uvažujete).

Úloha 2 (2 body)

Máme dané Bloom filtre pre množiny A a B, vytvorené s tou istou sadou

hešovacích funkcií (a teda aj s tou istou veľkosťou tabuľky).

- Ako môžeme z týchto dvoch Bloom filtrov zostrojiť Bloom filter pre

zjednotenie A a B? Bude taký istý, ako keby sme priamo vkladali prvky

zjednotenia do bežného Bloom filtra?

- Ako môžeme z týchto dvoch Bloom filtrov zostrojiť Bloom filter pre

prienik A a B? Bude taký istý, ako keby sme priamo vkladali prvky

prieniku do bežného Bloom filtra?

Úloha 3 (3 body)

Máme reťazce X a Y rovnakej dĺžky n, ktorých Hammingova vzdialenosť je 1.

- Aká môže byť v najhoršom prípade Hammingova vzdialenosť reťazcov

BWT(X$) a BWT(Y$)? Nájdite príklad, kde je táto vzdialenosť čo najväčšia

(ako funkcia n). Naopak, snažte sa dokázať aj horný odhad.

- Pomôcka: abeceda môže byť veľká (môže mať aj veľkosť n)

Úloha 4 (? bodov, podľa náročnosti)

Máme reťazce X a Y rovnakej dĺžky n, ktorých Hammingova vzdialenosť je 1.

- Aká môže byť v najhoršom prípade editačná vzdialenosť

reťazcov BWT(X$) a BWT(Y$)? Nájdite príklad, kde je táto vzdialenosť čo

najväčšia (ako funkcia n). Naopak, snažte sa dokázať aj horný odhad.

Séria 1, odovzdať do 14.3.

Úloha 1 (max 2 body)

V štruktúre RRR sme rozdelili reťazec na bloky dĺžky t2 a každému sme

v komprimovanom poli B priradili kód, pričom bloky s veľmi málo alebo

veľmi veľa jednotkami mali kratšie kódy ako bloky, v ktorých bol počet

jednotiek a núl probližne rovnaký. Namiesto tohto spôsobu môžeme

použiť nasledovný spôsob kompresie bitového reťazca. Pre každý z

typov bloku spočítame počet výskytov, t.j. koľko

blokov nášho reťazca má tento typ. Potom typy blokov zoradíme podľa

počtu výskytov a pripradíme im kódy tak, že najčastejšie sa

vyskytujúci typ bloku dostane ako kód prázdny reťazec, druhé dva

najčastejšie sa vyskytujúce typy blokov dostanú kódy 0 a 1, ďalšie

štyri typy dostanú kódy 00, 01, 10 a 11, ďalších 8 typov dostane kódy

dĺžky 3 atď.

typov bloku spočítame počet výskytov, t.j. koľko

blokov nášho reťazca má tento typ. Potom typy blokov zoradíme podľa

počtu výskytov a pripradíme im kódy tak, že najčastejšie sa

vyskytujúci typ bloku dostane ako kód prázdny reťazec, druhé dva

najčastejšie sa vyskytujúce typy blokov dostanú kódy 0 a 1, ďalšie

štyri typy dostanú kódy 00, 01, 10 a 11, ďalších 8 typov dostane kódy

dĺžky 3 atď.

Popíšte ako k takto komprimovanému reťazcu zostavíme všetky ďalšie

potrebné polia na to, aby sme mohli počítať rank v čase

O(1). Veľkosť vašej štruktúry by mala byť m+o(n), kde n je dĺžka

pôvodného binárneho reťazca a m dĺžka jeho komprimovanej verzie. Vaša

štruktúra sa asi bude podobať na štruktúru RRR z prednášky, ale

popíšte ju tak, aby text bol zrozumiteľný pre čitateľa, ktorý RRR

štruktúru nepozná, pozná však štruktúru pre nekomprimovaný rank.

Úloha 2 (max 2 body)

Označme B1 komprimovaný reťazec z úlohy 1, t.j zreťazenie kódov pre

jednotlivé bloky. Označme B2 komprimovaný reťazec z prednášky o

dátovej štruktúre RRR, t.j. zreťazenie odtlačkov (signature) pre

jednotlivé bloky. Nájdite príklad, kedy je B2 kratší ako B1 a naopak

príklad, pre ktorý je B1 oveľa kratší ako B2.

Poznámka: B1 ani B2 neobsahujú dosť informácie, aby sa z nich

samotných dal spätne rekonštruovať pôvodný binárny reťazec, lebo

nepoužíme bezprefixový kód. Huffmanovo kódovanie je bezprefixový kód,

lebo kód žiadneho znaku nie je prefixom kódu iného znaku.

Ak bonus za ďalšie body sa pokúste navrhnúť schému, v ktorej bude

komprimovaný reťazec najviac taký dlhý ako B2, ale ktorá búde spĺňať to, žo

okrem nej potrebujeme len  prídavnej

informácie pre každý blok na to, aby sme vedeli spätne určiť pôvodný

reťazec.

prídavnej

informácie pre každý blok na to, aby sme vedeli spätne určiť pôvodný

reťazec.

Úloha 3 (max 4 body)

V prednáške je uvedené bez dôkazu, že ak chceme počítať rank nad

väčšou abecedou, môžeme namiesto wavelet tree použiť RRR štruktúru pre

indikátorové bitové vektory jednotlivých znakov abecedy a že výsledná

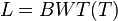

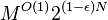

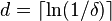

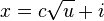

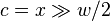

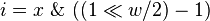

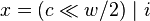

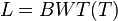

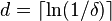

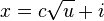

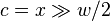

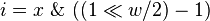

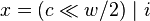

štruktúra bude mať veľkosť  . Dokážte toto tvrdenie. V tejto úlohe ocením aj vami spísaný

dôkaz naštudovaný z literatúry s uvedením zdroja. Ako počiatočný zdroj

môžete použiť prehľadový článok Navarro, Mäkinen (2007) Compressed

full-text

indexes [29]

(strana 30).

. Dokážte toto tvrdenie. V tejto úlohe ocením aj vami spísaný

dôkaz naštudovaný z literatúry s uvedením zdroja. Ako počiatočný zdroj

môžete použiť prehľadový článok Navarro, Mäkinen (2007) Compressed

full-text

indexes [29]

(strana 30).

Úloha 4 (max 3 body)

Uvažujme verziu štruktúry vector, ktorá používa ako parametre tri

reálne konštanty A,B,C>1. Ak pridávame prvok a v poli už nie je

miesto, zväčšíme veľkosť poľa z s na A*s. Naopak, ak zmažeme

prvok a počet prvkov klesne pod s/B, zmenšíme pole na s/C. V

knihe Cormen, Leiserson, Rivest and Stein Introduction to Algorithms

(kap. 17 v druhom vydaní) nájdete analýzu pre A=2, B=4 a C=2. Nájdite

množinu hodnôt parametrov A,B,C, pre ktoré pridávanie aj uberanie prvkov

funguje amortizovane v čase O(1).

Nemusíte charakterizovať všetky trojice parametrov, pre ktoré je

amortizovaný čas konštantný, ale nájdite nejakú množinu trojíc, pre

ktoré je to pravda. Ideálne každému parametru povolíte hodnoty z

nejakého intervalu, ktorý môže byť ohraničený konštantami alebo

funkciou iných parametrov. Zjavne napríklad musí platiť, že B>C.

Úsporné dátové štruktúry

Rank and select

Introduction to rank/select

Our goal is to represent a static set  , let m = |A|

, let m = |A|

Two natural representations:

- sorted array of elements of A

- bit vector of length n

Array Bit vector

Memory in bits m log n n

Is x in A? O(log m) O(1) rank(x)>rank(x-1)

max. y in A s.t. y<=x O(log m) O(n) select(rank(x))

i-th smallest element of A O(1) O(n) select(i)

how many elements of A are <=x O(log m) O(n) rank(x)

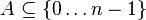

If m relatively large, e.g.  , bit array uses less memory

, bit array uses less memory

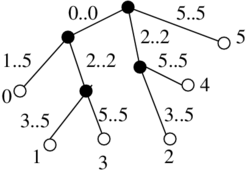

To get rank in O(1)

- trivial solution: keep rank(x) for each

, n log n bits

, n log n bits

- we will show that the bit vector of size n and o(n) additional bits are sufficient

- a simple practical solution for space reduction:

- choose value t

- array R of length n/t, R[i] = rank(i*t)

- rank(x) = R[floor(x/t)]+number of 1 bits in A[t*floor(x/t)+1..x]

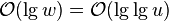

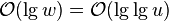

- memory n + (n/t)*lg(n) bits, time O(t)

- O(1) solution based on this idea, slightly more complex details

To get select in O(1)

- trivial solution is sorted array (see above)

- can be done in n+o(n) bits, more complex than rank

- practical compromise: binary search using log n calls of rank

Rank

- overview na slajde

- rank = rank of super-block + rank of block within superblock + rank of position within block

- block and superblock: integer division (or shifts of sizes power of 2)

- time O(1), memory n + O(n log log n / log n) bits

data structures:

- R1: Array of ranks at superblock boundaries

- R2: Array of ranks at block boundaries within superblocks

- R3: precomputed table of ranks for each type of block and each position within block of size t2

- B: bit array

rank(i):

- superblock = i/t1 (integer division)

- block = i/t2

- index = block*t2;

- type = B[index..index+t2-1]

- return R1[superblock]+R2[block]+R3[type, i%t2]

Select

- let t1 = lg n lglg n

- store select(t1 * i) for each i = 0..n/t1 memory O(n / t1 * lg n) = O(n/ lg lg n)

- divides bit vector into super-blocks of unequal size

- consider one such block of size r. Distinguish between small

super-block of size r<t1^2 and big super-block of size >= t1^2

- large super-block: store array of indices of 1 bits

- at most n/(t1 ^2) large super-blocks, each has t1 1 bits, each 1 bit needs lg n bits, overall O(n/lg lg n) bits

- small super-block:

- repeat the same with t2 = (lg lg n)^2

- store select(t2*i) within super-block for each i = 0..n/t2 memory O(n/t2 * lg lg n) = O(n/lg lg n)

- divides super-block into blocks, split blocks into small (size less than t2^2) and large

- for large blocks store relative indices of 1 bits: n/(t2 ^2) large

blocks, each has t2 1 bits, each 1 bit needs lg t1^2 = O(lg lg n) bits,

overall O(n/log log n)

- for small blocks of size at most t2^2, store as (t2^2)-bit integer,

lookup table of all answers. Size of table is O(2^(t2^2) * t2 *

log(t1)); t2^2 < (1/2) log n for large enough n, so 2^(t2^2) is

O(sqrt(n)), the rest is polylog

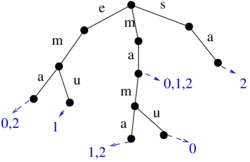

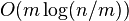

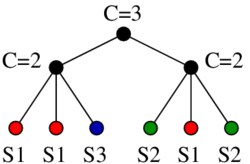

Wavelet tree: Rank over larger alphabets

- look at rank as a string operation over binary string B: count the number 1's in a prefix B[0..i]

- denote it more explicitly as rank_1(i)

- note: we can compute rank_0(i) as i+1-rank_1(i)

- instead of a binary string consider string S over a larger alphabet of size sigma

- rank_a(i): the number of occurrences of character a in a prefix S[0..i] of string S

- OPT is n lg sigma

- Use rank on binary strings as follows:

- rozdelime abecedu na dve casti Sigma_0 a Sigma_1

- Vytvorime bin. retazec B dlzky n: B[i]=j iff S[i] je v Sigma_j

- Predspracujeme B pre rank

- Vytvorime retazce S_0 a S_1, kde S_j obsahuje pismena z S, ktore su v Sigma_j, sucet dlzok je n

- Rekurzivne pokracujeme v deleni abecedy a retazcov, az kym nedostaneme abecedy velkosti 2, kde pouzijeme binarny rank

- rank_a(i) v tejto strukture:

- ak a in Sigma_j, i_2=rank_j(i) v retazci B

- pokracuj rekurzivne s vypoctom rank_a(i_2) v lavom alebo pravom podstrome

- Velkost: binarne retazce n log_2 sigma + struktury pre rank nad

bin. retazcami (mozem skonkatenovat na kazdej urovni a dostat o(n log

sigma) + O(sigma lg n) pre strom ako taky

- cas O(log sigma), robim jeden rank na kazdej urovni

- extrahovanie S[i] tiez v case O(log sigma)

- samotny retazec S teda nemusim ukladat

- nech j = B[i], i_2 = rank_j(i) v retazci B

- pokracuj rekurzivne s hladanim S_j[i2]

- original paper: Grossi, Gupta and Vitter 2003 High-order entropy-compressed text indexes

- survey G. Navarro, Wavelet Trees for All, Proceedings of 23rd Annual Symposium on Combinatorial Pattern Matching (CPM), 2012

- http://alexbowe.com/wavelet-trees/

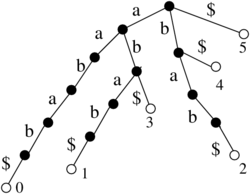

Rank in compressed string: RRR

- Raman, Raman, Rao, from their 2002 paper Succinct indexable

dictionaries with applications to encoding k-ary trees and multisets

- http://alexbowe.com/rrr/

class of a block: number of 1s

- R1: Array of ranks at superblock boundaries

- R2: Array of ranks at block boundaries within superblocks

- R3: precomputed table of ranks for each class, each signature within class and each position within block of size t2

- S1: Array of superblock starts in compressed bit array

- S2: Array of block offsets in compressed bit array

- C: class (the number of 1s) in each block

- L: size of signature for each class (ceil lg (t2 choose class))

- B: compressed bit array (concatenated signatures pf blocks)

rank(i):

- superblock = i/t1 (integer division)

- block = i/t2

- index = S1[superblock]+S2[block]

- class = C[block]

- length = L[class]

- signature = B[index..index+length-1]

- return R1[superblock]+R2[block]+R3[class, signature, i%t2]

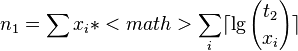

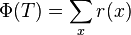

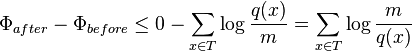

Analysis of RRR:

- Let S be a string in which a occurs n_a times

- Its entropy is H(S) = sum_a \frac{n_a}{n} \log \frac{n}{n_a}

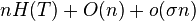

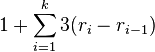

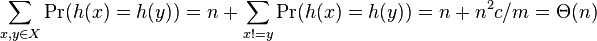

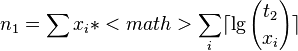

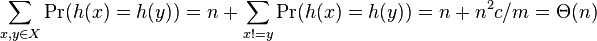

- let x_i be the number of 1s in block i, let n_1 be the overall number of 1s, i.e.

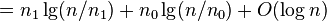

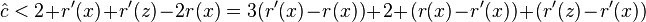

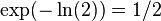

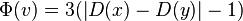

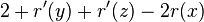

-

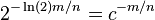

-

-

(choice of x_i in each block is subset of choice of n_1 overall)

(choice of x_i in each block is subset of choice of n_1 overall)

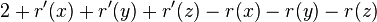

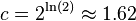

-

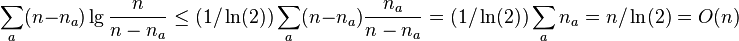

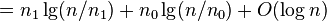

![\lg {n \choose n_{1}}=[\ln(n!)-\ln(n_{1}!)-\ln(n_{0}!))]/\ln(2)](vpds-archiv_files/37567c8ea7b8234e50e91ce5b70e6f53.png)

-

![=[n\ln(n)-n-n_{1}\ln(n_{1})+n_{1}-n_{0}\ln n_{0}+n_{0}+O(\log n)]/\ln(2)](vpds-archiv_files/80018e889469da04a42c3e6df1a54cb2.png)

-

(linear terms cancel out, n\ln(n) divided into two parts: n_0\ln(n) and n_1\ln(n))

(linear terms cancel out, n\ln(n) divided into two parts: n_0\ln(n) and n_1\ln(n))

-

Use in wavelet tree (see Navarro survey of wavelet trees):

- top level n0 zeroes, n1 ones, level 1: n00, n01, n10, n11

- top level entropy encoding uses n0 lg(n/n0) + n1 lg(n/n1) bits

- next level uses n00 lg(n0/n00) + n01 lg(n0/n01) + n10 lg(n1/n10) + n11 lg(n1/n11)

- add together n00 lg(n/n00) + n01 lg(n/n01) + n10 lg(n/n10) + n11 lg(n/n11)

- continue like this until you get sum_c n_c lg(n/n_c) which is nH(T)

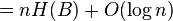

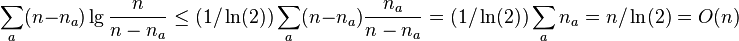

Instead of wavelet tree, store indicator vector for each character from alphabet in RRR string

-

![\sum _{a}[n_{a}\lg {\frac {n}{n_{a}}}+(n-n_{a})\lg {\frac {n}{n-n_{a}}}+o(n)]](vpds-archiv_files/e181bd123861abaead498500c0655320.png)

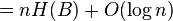

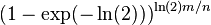

- the first terms in the sum equal to n H(T), the last terms sum to

, middle terms can be bound by O(n)

, middle terms can be bound by O(n)

-

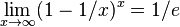

- We have used inequality ln(1+x)<=x for x>=-1

- Then

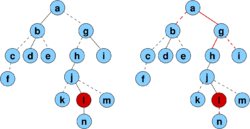

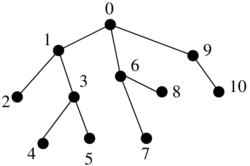

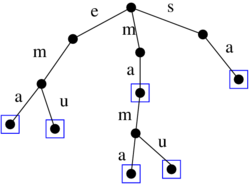

Binarny strom

- pridame pomocne listy tak, aby kazdy povodny vrchol bol vnut vrchol s 2 detmi

- ak sme mali n vrcholov, teraz mame n vnut. vrcholov a n+1 listov, t.j. 2n+1 vrcholov

- ocislujeme ich v level-order (prehladavanie do sirky) cislami 1..2n+1

- vrchol je reprezentovany tymto cislom

- datova struktura: bitovy vektor dlzky 2n+1, ktory ma na pozicii i 1 prave vtedy ak vrchol i je vnutorny vrchol

- nad tymto vektorom vybudujeme rank/select struktury v o(n) pridavnej pamati

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0

A B C D E . F . . G H . . . . . .

Lemma: Pre i-ty vnutorny vrchol (i-ta jednotka vo vektore, na pozicii select(i)) su jeho deti na poziciach 2i a 2i+1

- indukcia na i

- pre i=1 (koren) ma deti na poziciach 2 a 3

- deti i-teho vnutorneho vrcholu su v poradi hned po detoch (i-1)-veho

- dva pripady podla toho, ci (i-1)-vy a i-ty su na tej istej alebo

roznych urvniach, ale v oboch pripadoch medzi nimi len pomocne listy a

teda medzi ich detmi nic (obrazok)

- kedze deti (i-1)-veho su na poziciach podla IH 2i-2 a 2i-1, deti i-teho budu na 2i a 2i+1.

Dosledok:

- left_child(i) = 2 rank(i)

- right_child(i) = 2 rank(i)+1

- parent(i) = select(floor(i/2))

Ak chceme pouzit ako lexikograficky strom nad binarnou abecedou: potrebujeme zistit, ci vnut. vrchol zodpoveda slovu v mnozine

- jednoduchu fix s n dalsimi bitmi: z cisla vrchola 1..2n+1 zistime

rankom cislo vnut vrchola 0..n-1 a pre kazde si pamatame bit, ci je to

slovo z mnoziny

- da sa asi aj lepsie

Catalanove cisla

Ekvivalentne problemy:

- kolko je binarnych stromov s n vrcholmi?

- kolko je usporiadanych zakorenenych stromov s n+1 vrcholmi?

- kolko je dobre uzatvorkovanych vyrazov z n parov zatvoriek?

- kolko je postupnosti, ktore obsahuju n krat +1 a n krat -1 a pre ktore su vsetky prefixove sucty nezaporne?

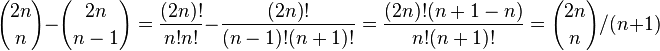

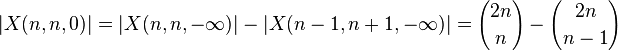

Chceme dokazat, ze odpoved je Catalanovo cislo <tex>C_n =

{2n\choose n}/(n+1)</tex> (C_0 = 1, C_1=1, C_2 = 2, C_3 = 5,...)

- Rekurencia <tex>T(n) = \sum_{i=0}^{n-1}

T(i)T(n-i-1)</tex> (nech najlavejsia zatvorka obsahuje vo vnutri i

parov), riesime metodami kombinatorickej analyzy (generujuce funkcie)

- Iny dokaz [30]

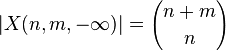

- Nech X(n,m,k) je mnozina vsetkych postupnosti dlzky n+m obsahujucich n +1, m -1 a takych ze kazdy prefixovy sucet je aspon k.

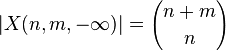

-

- my chceme |X(n,n,0)|

- nech Y = X(n,n,-infty)-X(n,n,0), t.j. vsetky zle postupnsti

- najdeme bijekciu medzi Y a X(n-1,n+1,-infty)

- vezmime postupnost z Y, najdime prvy zaporny prefixovy sucet (-1),

od toho bodu napravo zmenme znamienka, dostavame postupnost z

X(n-1,n+1,-infty) (obrazkovy dokaz so schodmi)

- naopak vezmime postupnost z X(n-1,n+1,-infty), najdeme prvy bod,

kde je zaporny prefixovy sucet (-1), od toho bodu napravo zmenme

znamienka, dostavame postupnost z Y

- tieto dve zobrazenia su navzajom inverzne, preto musi ist o bijekciu

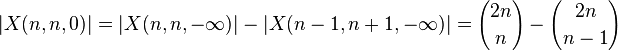

- preto

-

Connection to FM index (to be covered later in the course)

- Retazec dlzky n nad abecedou velkosti sigma mozeme ulozit pomocou n

lg sigma bitov (predpokladajme pre jednoduchost, ze sigma je mocnina 2)

- napr pre binarny retazec potrebuje n bitov

- Sufixove pole na umoznuje rychlo hladat vzorku, ale potrebuje n lg n

bitov, pripadne 3 n lg n, co je rychlejsie rastuca funkcia ako n

- sufixove stromy maju tiez Theta(n log n) bitov s vacsou konstantou

- vedeli by sme rychlo vyhladavat vzorku aj s ovela mensim indexom?

- oblast uspornych datovych struktur

Back to FM index

- jednoducha finta na zlepsenie pamate pre rank:

- ulozime si rank len pre niektore i, zvysne dopocitame na zaklade pocitania vyskytov v L (vydelime pamat k, vynasobime cas k)

- rank + L pomocou wavelet tree v n lg sigma + o(n log sigma) bitoch, hladanie vyskytov sa spomali na O(m log sigma)

- ako kompaktnejsie ulozit SA

- mozeme ulozit SA len pre niektore riadky, pre ine sa pomocou LF transformacie dostaneme k najblizsiemu riadku pre ktory mame SA

- let us say we want to print SA[i], but it is not stored, let denote its unknown value x

- L[i] is T[x-1]

- let j = LF[i], j is the row in which SA[j]=x-1

- if SA[j] stored, return SA[j]+1, otherwise continue in the same way

- ako presne ulozit "niektore riadky" ked su nerovnomerne rozmiestnene v SA (rovnomerne v T)?

- samotne L mozeme ulozit aj komprimovane s vhodnymi indexami, vid.

clanok od F a M alebo ho mame reprezentovane implicitne vo wavelet tree

Opakovanie, amortizovaná zložitosť

tieto poznamky este neexistuju, mozne je ich vytvorit preklopenim informacie z prezentacie

Prioritné rady

Nizsie su pracovne poznamky, ktore doplnuju informaciu z prezentacie, je mozne ich rozsirit, doplnit samotnou prezentaciou

Introduction to priority queues

Review

Operations Bin. heap Fib. heap

worst case amortized

MakeHeap() O(1) O(1)

Insert(H, x) O(log n) O(1)

Minimum(H) O(1) O(1)

ExtractMin(H) O(log n) O(log n)

Union(H1, H2) O(n) O(1)

DecreaseKey(H, x, k)

O(log n) O(1)

Delete(H, x) O(log n) O(log n)

Applications of priority queues

- job scheduling on a server (store jobs in a max-based priority

queue, always select the one with highest priority - needs operations

insert and extract_min, possibly also delete -needs a handle)

- event-driven simulation (store events, each with a time when it is

supposed to happen. Always extract one event, process it and as a result

potentially create new events - needs insert, extract_min Examples:

queue in a bank or store: random customer arrival times, random service

times per customer)

- finding intersections of line segments [31]

- Bentley–Ottmann algorithm - sweepline: binary search tree of line

intersections) plus a priority queue with events (start of segment, end

of segment, crossing)

- for n segments and k intersections do 2n+k inserts, 2n+k extractMin, overall O((n+k)log n) time

- heapsort (builds a heap from all elements or uses n time insert,

then n times extract_min -implies a lower bound on time of

insert+extract_min must be at least Omega(log n) in the comparison

model)

- aside: partial sorting - given n elements, print k in sorted order -

selection O(n), then sort in O(k log k), together O(n + k log k)

- incremental sorting: given n elements, build a data structure, then

support extract_min called k times, k unknown in advance, running time a

function of k and n

- call selection each time O(kn)

- heap (binary, Fibonacci etc) O(n + k log n) = O(n + k log k)

because if k>= sqrt n, log n = Theta(log k) and of k < sqrt n,

O(n) term dominates

- Kruskal's algorithm (can use sort, but instead we can use heap as

well, builds heap, then calls extract_min up to m times, but possibly

fewer, plus needs union-find set structure) O(m log n)

- process edges from smallest weight upwards, if it connects 2 components, add it. Finosh when we have a tree.

- Prim's algorithm (build heap, n times extract-min, m times

decrease_key - O(m log n) with binary heaps, O(m + n log n) with Fib

heaps)

- build a tree starting from one node. For each node outside tree keep the best cost to a node in a tree as a priority in a heap

- Dijkstra's algorithm for shortest paths (build heap, n times extract_min, m times decrease_key = the same as Prim's)

- keep nodes in a heap which do not have final distance. Set the

distance of minimum node to final, update distances of tis neighbors

Soft heap

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soft_heap

- Chazelle, B. 2000. The soft heap: an approximate priority queue with optimal error rate. J. ACM 47, 6 (Nov. 2000), 1012-1027.

- Kaplan, H. and Zwick, U. 2009. A simpler implementation and

analysis of Chazelle's soft heaps. In Proceedings of the Nineteenth

Annual ACM -SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms (New York, New York,

January 4––6, 2009). Symposium on Discrete Algorithms. Society for

Industrial and Applied Mathematics, Philadelphia, PA, 477-485. pdf

- provides constant amortized time for insert, union, findMin, delete

- but corrupts (increases) keys of up to epsilon*n elements, where

epsilon is a fixed parameter in (0,1/2) and n is the number of

insertions so far

- useful to obtain minimum spanning tree in O(m alpha(m,n)) where alpha is the inverse of Ackermann's function

Fibonacci heaps

Motivation

- To improve Dijkstra's shortes path algorithm from O(E*log V) to O(E + V*log V)

Structure of a Fibonacci heap

- Heap is collection of rooted trees, node degrees up to Deg(n) = O(log n)

- Min-heap property: Key in each non-root node ≥ key in its parent

- In each node store: key, other data, referrence for parent, first child, next and previous sibling, degree, binary mark

- In each heap: number of nodes n, pointers for: root with minimum key, first and last root

- Roots in a heap are connected by sibling pointers

- Non-root node is marked iff it lost a child since getting a parrent

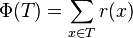

- Potential function: number of roots + 2 * number of marked nodes

Example of Fibonacci heap

Operations analysis

- n number of nodes in heap

- Deg(n) - maximum degree of a node x in a heap of size n

- potential function Φ = number of roots + 2 * number of marked nodes

- Amortized cost = real cost + Φ_after- Φ_before

Lazy operations with O(1) amortized time:

MakeHeap()

- create empty heap

- cost O(1), Φ= 0

- initialize H.n = [], H.min = null

Insert(H,x)

- insert node with value x into heap H:

- create new singleton node

- add this node to left of minimum pointer - update H.n

- update minimum pointer - H.min

- cost O(1), Φ= 1

Minimum(H)

- return minimum value from heap H - update H.min

- cost O(1), Φ= 0

Union(H1, H2)

- union two heaps

- concatenate root lists - update H.n, H.min

- cost O(1), Φ = 0

Other operations

ExtractMin(H)

- from heap H remove node with minimum value

- let x be root node with minimum key value, then it is in root list, and we have on him H.min pointer

- if x is singleton node (with no children), we will just extract him, return H.min and run consolidate(H) to find new H.min

- if x had children, before extracting x, we must add all children of

x to root list, update their parent pointer, then return H.min and run

then consolidate(H) to find new H.min

- what do consolite(H): changes structure of heap to achieve that no two nodes in root list have same degree, and finds H.min

- during one iteration througth root list, for each node in root list

it creates pointer to degree array, when it find two nodes with same

degree, it will link them together (HeapLink), thus node with higher key

value will be first left child of node with lower degree, also during

this iteration it is finding H.min

Analysis:

- t1 original count of nodes in the root list, t2 new count

- actual cost: O(Deg(n) + t1)

- O(Deg(n)) adding x's children into root list and updating H.min

- O(Deg(n) + t1) consolidating trees - computating is proportional to

size of root list, and number of roots decreases by one after each

merging (HeapLink)

- Amortized cost: O(Deg(n))

- t2 ≤ Deg(n) + 1, because each tree had different degree

- Δ Φ ≤ Deg(n) + 1 - t1

- let c be degree of z, c ≤ Deg(n) = O(log n)

- ExtractMin: adding children to root list: cost c, Δ Φ = c

- Consolidate: cost: t1 + Deg(n), Δ Φ = t2 - t1

- amortized t2 + Deg(n), but t2 ≤ Deg(n), therefore O(log n)

- Heaplink: cost 0, Φ = 0

1 ExtractMin (H) {

2 z = H.min

3 Add each child of z to root list of H ( update its parent )

4 Remove z from root list of H

5 Consolidate (H)

6 return z

7 }

1 Consolidate (H) {

2 create array A [ 0..Deg(H.n ) ], initialize with null

3 for (each node x in the root listt of H) {

4 while (A[x.degree] != null ) {

5 y = A[x.degree] ;

6 A[x.degree] = null ;

7 x = HeapLink (H, x, y)

8 }

9 A[x.degree] = x

10 }

11 traverse A, create root list of H, find H.min

12 }

1 HeapLink (H, x, y) {

2 if (x.key > y.key) exchange x and y

3 remove y from root list of H

4 make y a child of x, update x.degree

5 y.mark = false ;

6 return x

7 }

DecreaseKey(H,x,k)

- target: for node x in heap H change key value to k (it is decrease operation, so new value k must be lower than old value)

- find x and change it's kye value to k, there are three scenarios:

- 1. case: after changing key value for x, heap property is not

changed = value of node will be still higher than value of it's parent,

then update H.min

- 2. case: new value of node x break min-heap property and parent y (for node x) is not marked (hasn't yet lost a child), then cut link between x and y, mark y (now he lost child) and tree x add to root list, update H.min

- 3. case: new value of node x break min-heap property and parent y (for node x) is marked

(in history of heap he lost child), then cut link between x and y, tree

x add to root list (similar to previous 2. case, but...), cut link

between y and its parent z, add tree y to root list, and continue

recursively

- unmark each marked node added into root list

Analysis:

- t1 original count of nodes in the root list, t2 count of nodes in new heap

- m1 original count of marks in H, m2 count of marks in new heap

- Actual cost: O(c)

- O(1) for changing key value

- O(1) for each c cascading cuts and adding into root list

- Change in potential: O(1) - c

- t2 = t1 + c (adding c trees to root list)

- m2 ≤ m1 -c + 2 (every marked node, that was cuted was unmarked in root list, but last cut could posibly mark a node)

- Δ Φ ≤ c + 2*(-c + 2) = 4 - c

- Amortized cost: O(1)

DecreaseKey (H, x, k) {

2 x.key = k

3 y = x.parent

4 if (y != NULL && x.key < y.key) {

5 Cut(H, x, y)

6 CascadingCut (H, y)

7 }

8 update H.min

9 }

1 CascadingCut (H, y) {

2 z = y.parent

3 if (z != null) {

4 if (y.mark==false) y.mark = true

5 else {

6 Cut(H, y, z) ;

7 CascadingCut(H, z)

8 }

9 }

10 }

Delete(H,x)

- remove node x from heap H

- DecreaseKey(H,x, -infinity)

- ExtractMin(H)

- O(log n) amortized

Maximum degree Deg(n)

Proof of Lemma 3:

- Linking done only in Consolidate for 2 roots of equal degree.

- When y_j was linked, y_1,...y_{j-1} were children, so at that time x.degree >= j-1.

- Therefore at that time y_j.degree>= j-1

- Since then y_j lost at most 1 child, so y_j.degree >= j=2.

Proof of Lemma 4:

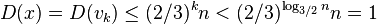

- Let D(x) be the size of subtree rooted at x

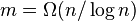

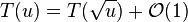

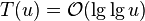

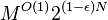

- Let s_k be the minimum size of a node with degree k in any Fibonacci heap (we will prove

)

)

- s_k<= s_{k+1}

- If we have a subtree of degree k+1, we can cut it from its parent and then cut away one child to get a smaller tree of degree k

- Let x be a node of degree k and size s_k

- Let y_1,...y_k be its children from earliest

- D(x) = s_k = 1 + sum_{j=1}^k D(y_j) >= 1 + D(y_1) + sum_{j=2}^k s_{y_j.degree}

- >= 2 + sum_{j=2}^k s_{j-2} (lemma 3)

- by induction on k: s_k >= F_{k+2}

- for k=0, s_0 = 1, F_2 = 1

- for k=1, s_1 = 2, F_3 = 1

- assume k>=2, s_i>=F_{i+2} for i<=k-1

- s_k >= 2+ sum_{j=2}^k s_{j-2} >= 2 + sum_{j=2}^k F_j (IH)

- = 1 + sum_{j=0}^k F_j = F_{k+2} (lemma 1)

Proof of Corollary:

- let x be a node of degree k in a Fibonacci heap with n nodes

- by lemma 4 n >= Φ^k

- therefore k<= log_Φ(n)

Exercise

- What sequence of operations will create a tree of depth n?

- Alternative delete (see slides)

Sources

- Michael L. Fredman, Robert E. Tarjan. "Fibonacci heaps and their

uses in improved network optimization algorithms."Journal of the ACM

1987

- Cormen, Thomas H., Charles E. Leiserson, Ronald L. Rivest, and Clifford Stein. Introduction to Algorithms. MIT Press 2001

Pairing heaps

- Simple and fast in practice

- hard to analyze amortized time

- Fredman, Michael L.; Sedgewick, Robert; Sleator, Daniel D.; Tarjan,

Robert E. (1986), "The pairing heap: a new form of self-adjusting

heap", Algorithmica 1 (1): 111–129

- Stasko, John T.; Vitter, Jeffrey S. (1987), "Pairing heaps:

experiments and analysis", Communications of the ACM 30 (3): 234–249

- Moret, Bernard M. E.; Shapiro, Henry D. (1991), "An empirical

analysis of algorithms for constructing a minimum spanning tree", Proc.

2nd Workshop on Algorithms and Data Structures, Lecture Notes in

Computer Science 519, Springer-Verlag, pp. 400–411

- Pettie, Seth (2005), "Towards a final analysis of pairing heaps",

Proc. 46th Annual IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, pp.

174–183 [32]

- a tree with arbitrary degrees

- each node pointer to the first child and next sibling (for delete

and decreaseKey also pointer to previous sibling or parent if first

child)

- each child has key >= key of parent

- linking two trees H1 and H2 s.t. H1 has smaller key:

- make H2 the first child of H1 (original first child of H1 is sibling of H2)

- subtrees thus ordered by age of linking from youngest to oldest

- extractMin is the most complex operation, the rest quite lazy

- insert: make a new tree of size 1, link with H

- union: link H1 and H2

- decreaseKey: cut x from its parent, decrease its key and link to H

- delete: cut x from parent, do extractMin on this tree, then link result to H

ExtractMin

- remove root, combine resulting trees to a new tree (actual cost up to n)

- start by linking pairs (1st and 2nd, 3rd and 4th,...), last may remain unpaired

- finally we link each remaining tree to the last one, starting from next-to-last back to the first (in the opposite order)

- other variants of linking were studied as well

O(log n) amortized time can be proved by a similar analysis as in splay trees (not covered in the course)

- imagine as binary tree - rename first child to left and next sibling to right

- D(x): number of descendants of node x, including x (size of a node)

- r(x): lg (D(x)) rank of a node

- potential of a tree - sum of ranks of all nodes

- details in Fredman et al 1986

- Better bounds in Pettie 2005: amortized O(log n) ExtractMin;

O(2^{2\sqrt{log log n}}) insert, union, decreaseKey; but decreaseKey not

constant as in Fibonacci heaps)

Meldable heaps (not covered in the course)

- Advantages of Fibonacci compared to binary heap: faster decreaseKey (important for Prim's and Dijkstra's), faster union

- meldable heaps support O(log n) union, but all standard operations

run in O(log n) time (except for build in O(n) and min in O(1))

- three versions: randomized, worst-case, amortized

- all of them use a binary tree similar to binary heap, but not always fully balanced

- min-heap property: key of child >= key of parent

- key operation is union

- insert: union of a single-node heap and original heap

- extract_min: remove root, union of its two subtrees

- delete and decreaseKey more problematic, different for different versions, need pointer to parent

- delete: cut away a node, union its two subtrees, hang back, may need some rebalancing

- decrease_key: use delete and insert (or cut away a node, decrease its key, union with the original tree)

Random meldable heap

Union(H1, H2) {

if (H1 == null) return H2;

if (H2 == null) return H1;

if (H1.key > H2.key) { exchange H1 and H2 }

// now we know H1.key <= H2.key

if (rand() % 2==1) {

H1.left = merge(H1.left, H2);

} else {

H1.right = merge(H1.right, H2);

}

return H1;

}

Analysis:

- random walk in each tree from root to a null pointer (external node)

- in each recursive call choose H1 or H2 based on key values, choose direction left or right randomly

- running time proportional to the sum of lengths of these random walks

Lemma: The expected length of a random walk in a any binary tree with n nodes is at most lg(n+1).

- let W be the length of the walk, E[W] its expected value.

- Induction on n. For n=0 we have E[W] = 0 = lg(n+1). Assume the lemma holds for all n'<n

- Let n1 be the size of the left subtree, n2 the size of right subtree. n = n1 + n2 + 1

- By the induction hypothesis E[W] <= 1 + (1/2)lg(n1+1) + (1/2)lg(n2+1)

- lg is a concave function, meaning that (lg(x)+lg(y))/2 <= lg((x+y)/2)

- E[W] <= 1 + lg((n1+n2+2)/2) = lg(n1+n2+2) = lg(n+1)

Corollary: The expected time of Union is O(log n)

A different proof of the Lemma via entropy

- add so called external nodes instead of null pointers

- let di be the depth of ith external node

- binary tree with n nodes has n+1 external nodes

- probability of random walk reaching external node i is pi = 2^{-di}, and so di = lg(1/pi)

- E[W] = sum_{i=0}^n d_i p_i = sum_{i=0}^n p_i lg(1/pi)

- we have obtained entropy of a distribution over n+1 values which is at most lg(n+1)

Leftist heaps

- Mehta and Sahni Chap. 5

- Crane, Clark Allan. "Linear lists and priority queues as balanced binary trees." (1972) (TR and thesis)

- let s(x) be distance from x to nearest external node

- s(x)=0 for external node x and s(x) = min(s(x.left), s(x.right))+1 for internal node x

- height-biased leftist tree is a binary tree in which for every internal node x we have s(x.left)>=s(x.right)

- therefore in such a tree s(x) = s(x.right)+1

Union(H1, H2) {

if (H1 == null) return H2;

if (H2 == null) return H1;

if (H1.key > H2.key) { exchange H1 and H2 }

// now we know H1.key <= H2.key

HN = Union(H1.right, H2);

if(H1.left != null && HN.left.s <= H1.s) {

return new node(H1.data, H1.left, HN)

} else {

return new node(H1.data, HN, H1.left)

}

}

- note: s value kept in each node, recomputed in new node(...) using s(x) = s(x.right)+1

- recursion descends only along right edges

Lemma: (a) subtree with root x has at least 2^{s(x)}-1 nodes (b) if a

subtree with root x has n nodes, s(x)<=lg(n+1) (c) the length of the

path from node x using only edges to right child is s(x)

- (a) all levels up to s(x) are filled with nodes, therefore the number of nodes is at least 1+2+4+...+2^{s(x)-1} = 2^{s(x)}-1

- (b) an easy corollary of a (n>=2^s-1 => s<-lg(n+1))

- (c) implied by height-biased leftist tree property (in each step to the right, s(x) decreases by at least 1)

Corollary: Union takes O(log n) time

- recursive calls along right edges from both roots - at most s(x)<=lg(n+1) such edges in a tree of size n

Skew Heaps

- self-adjusting version of leftist heaps, no balancing values stored in nodes

- Mehta and Sahni Chap. 6

Union(H1, H2) {

if (H1 == null) return H2;

if (H2 == null) return H1;

if (H1.key > H2.key) { exchange H1 and H2 }

// now we know H1.root.key <= H2.root.key

HN = Union(H1.right, H2);

return new node(H1.data, HN, H1.left)

}

Recall: Heavy-light decomposition from Link/cut trees

- D(x): number of descendants of node x, including x (size of a node)

- An edge from v to its parent p is called heavy if D(v)> D(p)/2, otherwise it is light.

Observations:

- each path from v to root at most lg n light edges because with each

light edge the size of the subtree goes down by at least 1/2

- each node has at most one child connected to it by a heavy edge

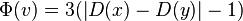

Potential function: the number of heavy right edges (right edge is an edge to a right child)

Amortized analysis of union:

- Consider one recursive call. Let left child of H1 be A, right child B

- Imagine cutting edges from root of H1 to it children A and B before

calling recursion and creating new edges to Union(B,H2) and A after

recursive call

- Let real cost of one recursive call be 1

- If edge to H1.B was heavy

- cutting edges has delta Phi = -1

- adding edges back does not create a heavy right edge, therefore delta Phi = 0

- amortized cost is 0

- If edge to H1.B was light

- cutting edges has delta Phi = 0

- adding edges creates at most one heavy right edge, therefore delta Phi <= 1

- amortized cost is <= 2

All light edges we encounter in the algorithm are on the rightmost

path in one of the two heaps, which means there are at most 2 lg n of

them (lg n in each heap). This gives us amortized cost at most 4 lg n.

Amortizované vyhľadávacie stromy a link-cut stromy

Predbežná verzia poznámok, nebojte sa upravovať: pripojiť informácie z prezentácie, pridať viac vysvetľujúceho textu a pod.

Scapegoat trees

Introduction

- Lazy amortized binary search trees

- Relatively simple to implement

- Do not require balancing information stored in nodes (needs only left child, right child and key)

- Insert and delete O(log n) amortized

- Search O(log n) worst-case

- Height of tree always O(log n)

- For now let us consider only insert and search

- Store the total number of nodes n

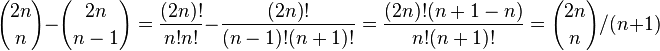

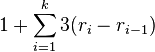

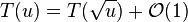

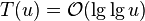

- Invariant: keep the height of the tree at most

- Note: 3/2 can be changed to 1/alpha for alpha in (1/2,1)

- Let D(v) denotes the size (the number of nodes) of subtree rooted at v

Insert

- Start with a usual insert, as in unbalanced BST

- If a node inserted at higher depth, restructure as follows

- Follow the path back from inserted node x to the root

- Find the first node u on this path and its parent p for which D(u)/D(p) > 2/3

- This means that node p is very unbalanced - one of its children containing more than 2/3 of the total subtree size

- Node p will be called the scapegoat

- We will show later that a scapegoat always exists on the path to root (Lemma 1)

- Completely rebuild subtree rooted at p so that it contains the same values but is completely balanced

- This is done by traversing entire subtree in inorder, storing keys in an array (sorted)

- Root of the subtree will be the median of the array, left and right subtrees constructed recursively

- Running time O(D(p))

- This can be also done using linked lists built from right pointers in the node, with only O(log n) auxiliary memory for stack

- The height was before violated by 1, this improves it at least by 1, so the invariant is satisfied

- Why we always get improvement by at least 1:

- Let v be a sibling of u, if no sibling set D(v)=0

- D(u) > 2D(p)/3 > D(p)/3 >= D(p)-D(u), do D(p)-D(u)<=D(u)-1

- D(v) = D(p)-D(u)-1 <= D(u)-2

- so the sizes of left and right subtree of p differ by at least 2

- Let height of D(u) be h. The last level contains only the last inserted node, so D(u)-1 nodes can fit to h-1 levels

- In the rebuilt tree, the size of left and right subtree will differ

by at most 1 and thus both will have at most D(u)-1 nodes and so they

can fit into h-1 levels; the hight will thus decrease by at least 1

- Finding the scapegoat also takes O(D(p)) because we need to compute D(v) at every visited node

- Each computation in time O(D(v))

- But up to node u, child has always size at most 2/3 of parent

- Therefore sizes of subtrees for which we compute D(v) grow

exponentially (geometric sum) and are dominated by the last 2

computations of D(u) and D(p)

- TODO: formulate lemma to imply both this and Lemma 1

Lemma 1: If a node x in a tree with n nodes is in depth greater than  , then on the path from x to the root there is a node u and it parent p such that D(u)/D(p) > 2/3

, then on the path from x to the root there is a node u and it parent p such that D(u)/D(p) > 2/3

Proof:

- Assume that this is not the case, let nodes nodes on the path from x

to root be v_k, v_{k-1},...v_0, where v_k=x and v_0 is the root and

- D(v_0) = n.

- Since D(v_i)<=2/3 D(v_{i-1}), we have D(v_i) <= (2/3)^i n.

-

- Thus we have D(x)<1, which is a contradiction, because the subtree rooted at x contains at least one node

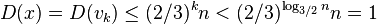

Amortized analysis of insert

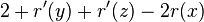

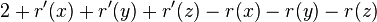

- Potential of a node v with children x,y:

-

if |D(x)-D(y)| <= 1 (sizes of subtrees approximately the same)

if |D(x)-D(y)| <= 1 (sizes of subtrees approximately the same)

-

- Potential of tree: sum of potentials of subtrees

- Insert in depth d except rebuilding:

- real cost O(d)

- change of Phi at most 3d, because potential increases by at most 3

for nodes on the path to newly inserted vertex and does not change

elsewhere

- amortized cost O(d) = O(log n)

- Rebuilding:

- real cost m = D(p) where p is the scapegoat

- let u and v be children of p before rebuilt, D(u)>D(v)

- m = D(p)=D(u)+D(v)+1, D(u)>2m/3, D(v)<m/3, D(u)-D(v)>1/3 m

- before rebuilt Phi(p) > m-3

- potential in all nodes in the rebuilt subtree is 0

- change of Phi <= -m +3

- amortized cost O(1)

Delete

- Very lazy version

- Do not delete nodes, only mark them as deleted

- Keep counter of deleted nodes

- When more than half nodes marked as deleted, completely rebuild the whole tree without them

- Each lazy delete pays a constant towards future rebuild. At least n/2 deleted before next rebuild.

- Variant: delete nodes as in unbalanced binary tree. This never increases height. Rebuild when many nodes deleted.

Uses of scapegoat trees

Scapegoat trees are useful if nodes of tree hold auxiliary information which is hard to rebuild after rotation

- we will see an example in range trees used in geometry

- another simple example from Morin's book Open Data Structures:

- we want to maintain a sequence of elements (conceptually something like a linked list)

- insert gets a pointer to one node of the list and inserts a new node before it, returns pointer to the new node

- compare gets pointers to two nodes from the same list and decided which is earlier in the list

- idea: store in a scapegoat tree, key is the position in the list.

Each node holds the path from the root as a binary number stored in an

int (height is logarithmic, so it should fit)

- Exercise: details?

Sources

Splay trees

Intuition and examples

- if height of tree is large, search is expensive, we use potential

- potential of path-like trees should be large, balanced trees smaller

- what happens if we apply splay on a leaf on a path?

- side benefit: if we search for some nodes more often, they tend to be near the root

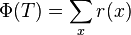

Amortized analysis of splaying

- real cost: number of rotations

- D(x): number of descendants of node x, including x (size of a node)

- r(x): lg (D(x)) rank of a node (lg denotes log_2)

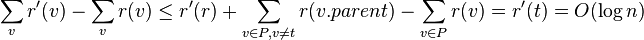

-

- Exercise: asymptotically estimate potential of a path and balanced tree with n nodes

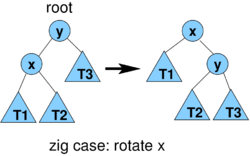

Lemma1 (proof later): consider one step of splaying x (1 or 2 rotations)

- let r(x) be rank of x before splaying, r'(x) after splaying

- amortized cost of one step of splaying is at most

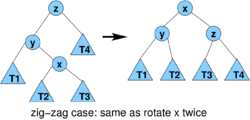

- 3(r'(x)-r(x)) for zig-zag and zig-zig

- 3(r'(x)-r(x))+1 for zig

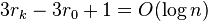

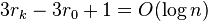

Lemma2: Amortized cost of splaying x to the root in a tree with n nodes is O(log n)

- Let r_i be rank of x after i steps of splaying, let k be the number of steps

- amortized cost is at most

- (use Lemma 1, +1 is from the last step of splaying)

- telescopic sum, terms cancel, we get

Theorem: Amortized cost of insert, search and delete in splay tree is O(log n)

- search:

- walk down to x, then splay x (if x not found, splay the last visited node)

- amortized cost is O(log n)

- insert:

- insert x as in normal binary search tree, then splay x.

- Inserting increase rank of all nodes on the path P from root t to x

- consider node v and its parent p on this path P

- D'(v) = 1 + D(v) <= D(p)

- r'(v) <= r(p)

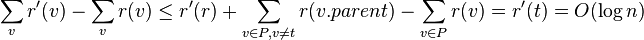

- change in potential

- amortized cost of insert + splaying is thus O(log n)

- delete:

- delete x as from binary search tree (may in fact delete node for

predecessor or successor of x), then splay parent of deleted node

- deletion itself decreases potential, amortized cost of splaying is O(log n)

- amortized cost is O(log n)

- overall time in each operation proportional to the length of the

path traversed and therefore to the number of rotations done in splaying

- therefore amortized time O(log n) for each operation.

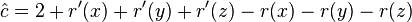

Proof of Lemma 1:

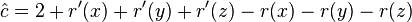

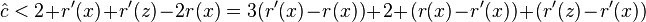

- case zig: cost 1, r'(x) = r(y), all nodes except x and y keep their ranks

- amortized cost

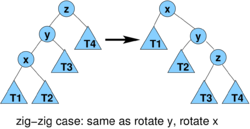

- case zig-zig: cost 2,

- amortized cost

- we have r'(x) = r(z), r'(y)< r'(x), r(y)> r(x)

- therefore

- therefore we need (r(x)-r'(x))+(r'(z)-r'(x))<=-2 or lg (D(x)/D'(x)) + lg (D'(z)/D'(x)) <= -2

- observe that D(x)+D'(z) <= D'(x) (in fact D'(x)=D(x)+D(z)+1 where +1 corresponds to node y)

- let a = D(x)/D'(x), b = D'(z)/D'(x), we have a+b<=1

- binary logarithm is concave, i.e. (lg(a)+lg(b))/2 <= lg((a+b)/2)

- and if a+b<=1, lg((a+b)/2) <= lg(1/2) = -1

- lg (D(x)/D'(x)) + lg (D'(z)/D'(x)) = lg a + lg b <= -2

- case zig-zag is analogous

- amortized cost

- r'(x) = r(z), r(x)<=r(y)

- therefore am. cost at most

- we will prove that 2 <= 2r'(x)-r'(y)-r'(z) and this will imply amortized cost is at most 2(r'(x)-r(x))

- we have D'(y)+D'(z) <= D'(x), use the same logarithmic trick as before

Adaptability of splay trees

If some element is accessed frequently, it tends to be located near the root, making access time shorter

Weighted potential function

- Assign each node x fixed weight w(x)>0

- D(x): the sum of weights in the subtree rooted at x

- r(x) = lg(D(x)) (rank of node x)

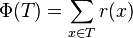

-

Weighted version of Lemma 2:

- Amortized cost of splaying x to the root is 1+3(r(t)-r(x)) =

O(1+log (D(t)/D(x))), where t is the original root before splaying.

- Proof similar to Lemma 2

- By setting weight 1 for every node we get Lemma 2 as a corollary

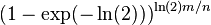

Static optimality theorem:

- Starting with a tree with n nodes, execute a sequence of m find operations, where find(x) is done q(x)>=1 times.

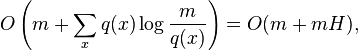

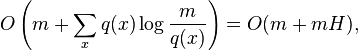

- The total access time is

-

- where H is the entropy of the sequence of operations.

Proof:

- Set w(x)=q(x)/m. In weighted Lemma 2, w(T)<=1, D(x)>=w(x)=q(x)/m.

- Amortized cost of splaying x is thus O(1+log(m/q(x))); this is done q(x) times.

- After summing this expression for all operations we get the stated bound.

- However, we have to add a decrease of potential (using up money from the bank)

- with these weights, D(x)<=1, r(x)<=0 and thus Phi(x)<=0

- on the other hand, D(x)>w(x),

-

- Since q(x)>=1 and log(m/q(x))>=0, this is within stated upper bound

Note:

- Lower bound for a static tree is

(see Melhorn 1975); our tree not static

(see Melhorn 1975); our tree not static

Sequential access theorem:

- Starting from any tree with n nodes, splaying each node to the root

once in the increasing order of the keys has total time O(n).

- Proved by Tarjan 1985, improved proof Elmasry 2004 (proof not covered in the course)

- Trivial upper bound from our amortized analysis is O(n log n)

Collection of splay trees

Image now a collection of splay trees. The following operations can

be done in O(log n) amortized time (each operation gets pointer to a

node)

- findMin(v): find the minimum element in a tree containing v and make it root of that tree

- splay v, follow left pointers to min m, splay m, return m

- join(v1, v2): all elements in tree of v1 must be smaller than all elements in tree of v2. Join these two trees into one

- m = findMin(v2), splay(v1), connect v1 as a left child of m, return m

- connecting increases rank of m by at most log n

- splitAfter(x) - split tree containing v into 2 trees, one

containing keys <=x, one containing keys > x, return root of the

second tree

- splay(v), then cut away its right child and return it

- decreases rank of v

- splitBefore(v) - split tree containing v into 2 trees, one

containing keys <x, one containing keys >=x, return root of the

first tree

- analogous, cut away left child

Sources

- Sleator, Daniel Dominic, and Robert Endre Tarjan. "Self-adjusting

binary search trees." Journal of the ACM 32, no. 3 (1985): 652-686.

- Original publication of splay trees.

- Elmasry A. On the sequential access theorem and deque conjecture

for splay trees. Theoretical Computer Science. 2004 Apr

10;314(3):459-66.

- Proof of an improved version of the sequential access theorem

- Mehlhorn K. Nearly optimal binary search trees. Acta Informatica. 1975 Dec 1;5(4):287-95.

- Proof of the lower bound on static optma binary search trees (theorem 2, page 292)

Link-cut trees

Union/find

Maintains a collection of disjoint sets, supports operations

- union(v, w): connects sets containing v and w

- find(v): returns representative element of the set containing v (can be used to test of v and w are in the same set)

Can be used to maintain connected components if we add edges to the

graph, also useful in Kruskal's algorithm for minimum spanning tree

Implementation

- each set represented by a (non-binary) tree, in which each node v has a pointer to its parent v.p

- find(v) follows pointers to the root of the tree, returns the root

- union calls find for v and w and joins one with the other

- if we keep track of tree height and always join shorter tree below

higher tree plus do path compression, we get amortized time

O(alpha(m+n,n)) where alpha is inverse ackermann function, extremely

slowly growing (n = number of elements, m = number of queries)

Exercise: implement as a collection of splay trees

- hint: want to use join for union, but what about the keys?

- splay trees actually do not need to store key values if we do not search

Link/cut trees

Maintains a collection of disjoint rooted trees on n nodes

- findRoot(v) find root of tree containing v

- link(v,w) w a root, v not in tree of w, make w a child of v

- cut(v) cut edge connecting v to its parent (v not a root)

O(log n) amortized per operation. We will show O(log^2) amortized

time. Can be also modified to support these operations in worst-case

O(log n) time, add more operations e.g. with weights in nodes.

Similar as union-find, but adds cut plus we cannot rearrange trees as needed as in union-find

Simpler version for paths

Simpler version for paths (imagine them as going upwards):

- findPathHead(v) - highest element on path containing v

- linkPaths(v, w) - join paths containing v and w (head of v's path will remain head)

- splitPathAbove(v) - remove edge connecting v to its parent p, return some node in the path containing p

- splitPathBelow(v) - remove edge connecting v to its child c, return some node in the path containing c

Can be done by splay trees

- keep each path in a splay tree, using position as a key (not stored anywhere)

- findPathHead(v): findMin(v)

- linkPaths(v, w): join(v, w)